Good research habits and methodologies could possibly exponentially magnify the outcomes of one’s research efforts. But how can one develop these habits and methodologies? The act of research itself obviously helps. However, such trial-and-error training of research skills could be inefficient and easily forgettable in the long run, at least from my own experience. When Yitao shared with me an article by John Schulman where John mentioned how his habit of keeping a research notebook was tremendously helpful, I started to keep a research log myself. In this blog post, I will share what I learned from logging research and how maintaining a daily research log, complemented by weekly reviews, significantly increases the effectiveness of learning to do better research from one’s everyday research experience.

Why keep a research log

Amplify good research habits and do iterative refinement. Athletes watch replays to spot both their strengths and weaknesses. Similarly, maintaining a daily log of research activities allows one to observe their patterns and do film study. For example, consider the following questions that a research log could answer:

- Where did I gather the most important information (e.g., paper updates and insightful blog posts) last week? The answer could guide a better balance of information sources.

- How did I discover that exciting idea? By chatting with someone, reading papers, or running/analyzing experiments? The answer could lead to better time management.

- What made this week better than the last week? The answer could lead to the discovery of useful habits that particularly work for you.

Answering these questions turns the log into a personal handbook of dos and don’ts explicitly tailored to one’s working style and research approach. Assuming that there’s always something to learn, then when the habits learned from one’s research log are iteratively practiced, we can obtain research logs with increasing quality and learn even more from them.

Learning from past data for better long-term planning. The research log is a massive database of trajectories of research decisions. It records all explorations, failures, and sometimes unexpected successes. Reviewing the log makes it easier to identify trends over time. Consider the following questions:

- What bugs most often occur in your code?

- What experiments provided valuable insights for answering a research question?

- How long do tasks genuinely take versus the initial estimates?

- How does the focus of a project evolve throughout its development?

These data are unreasonably easy to collect (just write down what you did on the log with less than 10s) but become invaluable for decision-making, such as what experiment to run next to optimize information gain and which future project or research agenda so that it is realistically feasible.

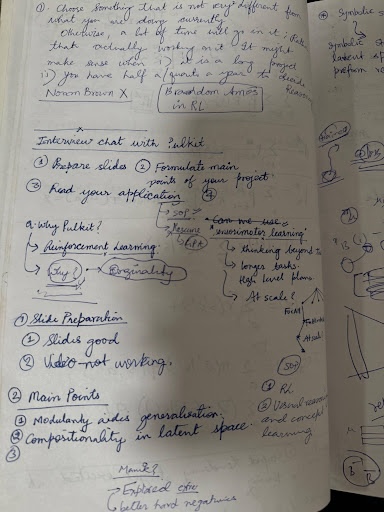

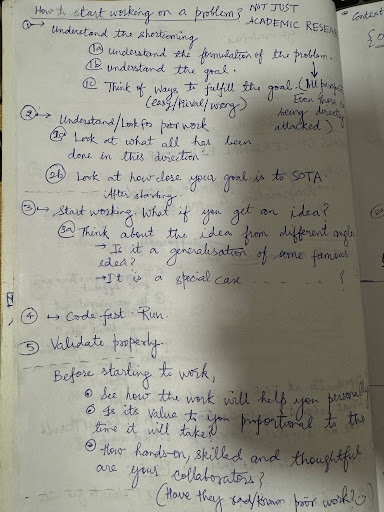

Sharing knowledge. If you’re willing to share your notebook with others, it can greatly help them improve their research practices. Sharing your thought processes, problem-solving approaches, and even struggles can provide valuable insights to fellow researchers, especially those who are just starting their journey. For example, below are two pages from a notebook that I got from BAIR. The left page shows detailed reasoning process of the author, and the right page shows a summary of how to start working on a research problem.

Some practical tips for logging

What to write down? A research log should capture at least three levels of information:

- Level 0 (facts): Record experiments you run, papers you read, bugs and fixes, and anything that happens during the research process. The key is to dump everything you did efficiently.

- Level 1 (thoughts & emotions): Write down how specific decisions are made, the chain-of-thought behind them, any intuitions about experiment results. This level is about capturing the thought process behind the facts.

- Level 2 (reflection): These are like your second-order thoughts on the research trajectories you’ve collected. I often do this once a week or sometimes at the end of a day.

Organizing the log. I use Notion to keep my research log. I create two databases for daily and weekly logs respectively. In the daily database, I have a subpage for each day, where I divide the log into three sections: What to do next, What was done, and Random ideas. The first section is like a to-do list, where unfinished tasks will be passed to the next day’s log. The second section contains every possible detail of what I did in a day (level 0 and 1). The third section records any ideas I got from a paper, a chat with someone, or a morning shower.

Using AI to understand the log. The good thing about Notion is that you can search in your log and ask questions about past events easily with Notion AI. I also tried prompting GPT-4 to generate a summarization of all my random ideas. The results are not that surprising, but they are kind of related and serve as a good summary of what came to my mind in the past week. Perhaps as AIs scale, they can do better on this and help us on scalable oversight of ourselves. Moreover, if we can collect enough high-quality data, maybe we can even train a model to predict what we should do next based on our past logs, resulting in an automatic (superhuman-)AI researcher.

Well but that’s a bit far-fetched. For now, GPT-4 only gives me a vague summary like this:

This week’s summary of your research ideas from your logs reveals a broad range of innovative thoughts, experimentation reflections, and speculative inquiries that explore the intersection of machine learning models, human studies, and the alignment problem. The themes covered this week encompass experiments on model performance, leveraging external tools for scalable supervision, and conceptual explorations in model alignment and reward modeling.

Model Experiments and Performance:

- Your work included running experiments on various GPT model scales, revealing only slight performance improvements with increased model size.

- Investigations into why weakly supervised models perform differently led to insights about error imitation and the potential benefits of using external knowledge bases or tools in reward modeling.

Exploration of External Tools and Knowledge Bases:

- You pondered the integration of external tools or databases to enhance model evaluations, especially in the context of reward modeling, and considered how this could lead to more efficient process-supervised reward models.

- The possibility of utilizing external tools to check alignment in tasks like the grid world task, where models’ latent goals can be quantifiably aligned, was another avenue of thought.

Conceptual Inquiries and Future Directions:

- You questioned the potential for human studies to supervise models that surpass human performance in specific tasks, suggesting a focus away from college students towards middle or high school students for such experiments.

- The concept of comparing weak to strong generalization (W2SG) techniques with weak to hard generalization (W2H(ard)G) was critically examined, especially in terms of measuring difficulty in reward modeling and the implications for tasks beyond clear-cut right or wrong answers.

Reward Modeling and Debate Techniques:

- Your reflections include considerations on the utility of few-shot prompting in reward modeling scenarios and the exploration of whether techniques from W2SG could be used for model self-improvement or in contexts where human labels are noisy.

Generative Tasks and Model Rationale:

- There was an interesting idea about the self-explanatory nature of generative tasks, where the rationale of a model’s decisions could be inspected to decide on label changes, using log probability as a communication method to infer belief in the strong model’s outputs.

In conclusion, your weekly log reflects a deep engagement with critical questions at the forefront of AI research. Your exploration spans practical issues in model performance and experimental methodology to broader theoretical inquiries about model alignment, the role of external tools, and the potential for human studies to inform model supervision. This synthesis of ideas points to a rich, multi-faceted approach to tackling some of the most pressing challenges in AI and machine learning research today.